The multinational clients who were with MEMAS before the establishment of Intermarkets realized the opportunities posed by the merger and the claim of being the first regional advertising agency in the Middle East. Clients like Johnson & Johnson, Unilever, Reckitt & Colman, Cadbury, and many others saw how a solution for servicing Syria was quickly arranged when Unilever needed it. However, most of these clients seemed keen to have robust, long-term, and dynamic solutions for their promotional needs in the oil-rich Gulf states. This was the time post the oil boom that global manufacturers began to look in the direction of these markets, which held the promise of real growth.

On top of the growth list was Saudi Arabia. However, clients were aware of the difficulties they faced every time they attempted to place their own people in that market. In fact, none of the multinational clients had succeeded in establishing a representative office in Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom was considered a hardship market for expats, and it was almost impossible to persuade candidates to accept a job in Jeddah or Riyadh, no matter how generous the package. A solution had to be found, so these companies posted their people to Bahrain, travelling to Saudi Arabia for the working week and retiring to Bahrain for the weekends. This way, Bahrain became the living hub for those expats and their families. It also allowed small Lower Gulf representative offices to be established for secretarial and mail support.

At Intermarkets, the decision was made to establish a branch in Bahrain to be close to the agency’s Saudi clients. An intensive search was launched to hire a manager to set up Intermarkets Bahrain and manage it. A couple of weeks after this decision was made, I was called into the office of Erwin Guerrovich. Sitting across the desk from Erwin was a young man with dark black wavy hair. He was wearing a navy-blue suit, which clearly showed an American cut. But what struck me most were the cowboy boots he was wearing, at a time when all of us were in sneakers or moccasins as it was the beginning of spring. The visitor was introduced to me as Eddie (for Edmond) Moutran, the candidate being considered for the Bahrain assignment. Guerrovich attempted to repeat Moutran’s self-introduction, but he interjected, correcting names and dates, which was outside of normal conversation etiquette in the Intermarkets corner office. When Moutran left, Erwin asked for my evaluation of the candidate following our brief encounter, and I was complimentary, since I saw an ally in this American-educated newcomer who would surely help to break the “Jesuit Spirit” that had started to creep in from the old MEMAS team into Intermarkets.

Eddie Moutran accepted the Intermarkets offer, insisting that the agency should remember that he had no past advertising experience, which required us to remain close to coach and guide him until he mastered the profession and reached a stage where clients were pleased with his performance. In what would become his normal pushy style, he insisted on being allowed to place long distance calls every time he had a question to ask, stressing that he would not want to be criticized for the high telephone bills at any time in the future. In the same token, he demanded to be allowed to travel to Beirut every time he and the clients felt a need to do that. Erwin and his vice presidents seemed to be impressed with Moutran’s confident and bold approach, so they all agreed to grant him his requests. Then, on the day Eddie came to the agency to countersign his appointment letter, Erwin confirmed Intermarkets’ acceptance of his requests and informed him that I would be his main contact, coach, and trainer. This is how our journey together started.

Every day, Eddie came to the agency, and we spent time reviewing all the information that could help make him a convincing Middle East advertising practitioner in the shortest possible time. Among all the topics we covered – because our days were packed with dialogue rather than lecturing – was a quick survey of the Middle East advertising scene, with a concentration on the role of Lebanese publishers and journalists in developing the Arab media scene. Then we narrowed in on Eddie’s future markets of operation, starting with Bahrain and its current role as the gateway to Saudi Arabia. We reviewed the operations of our multinational clients who were active in both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, with the involvement of Salim Sednaoui and Raymond Accad, who were responsible for these clients. During this crash orientation period, Eddie became my shadow. He participated in all my Shell, Ceylon Tea and Johnson Wax meetings, as well as my internal meetings with the creative, media, traffic, and finance departments. Eddie mastered the agency’s systems and procedures, developing close friendships across all departments at the Beirut office.

Then one day, I felt we had had enough restaurant lunches and sandwiches together and it was time to upgrade the business relationship to a familial one, so I invited Eddie to lunch at my home in Aley. Before leaving for the office early in the morning, my young wife, Grace, and I reviewed what she was planning to serve, as she was a new cook, and I wanted my guest to leave our house with the best impression. When I returned with Eddie at lunchtime, I rang the doorbell and stepped aside to allow my guest to enter first. My wife opened the door and instantly two screams were heard. My wife exclaimed with great surprise: “Edmond?!!” Then my guest screamed at the top of his voice: “Grace?!!” To the surprise of us all, Eddie had been to the Beirut Baptist School and had attended the same class as Grace’s brother, Salam, so he remembered her as the younger sister of his classmate, while she remembered Eddie as the friend of her brother and elder sister, Freeda. This surprise encounter made our lunch an opportunity for more bonding and laughter. It also took the relationship with my new office colleague to a totally different level, which continued to endure until his death in 2021.

The plan for Intermarkets to set-up in Bahrain and coordinate its Saudi Arabian business from there had started to spread amongst the agency’s active clients, who all encouraged the plan. Johnson & Johnson showed the most spontaneous interest, as it recommended its Bahrain distributor to act as national partner or sponsor for the new entity. This brought us into contact with Ahmad Youssef Mahmoud Husain, the owner of the pharmacy established by his father in 1935. Ahmad took over from his father and became known for his active role in modernizing the family business. A business agreement was quickly established between Ahmad Youssef Mahmoud Husain and Intermarkets following Erwin Guerrovich’s visit to Bahrain in the company of Eddie. Eddie was introduced to the Bahraini partner, who welcomed him into a small office located up some steep stairs above the pharmacy in the heart of old Manama, near the historic Bab Al Bahrain. The first employee at Intermarkets Bahrain was a Sri Lankan PA, who over the years became the mother of the agency.

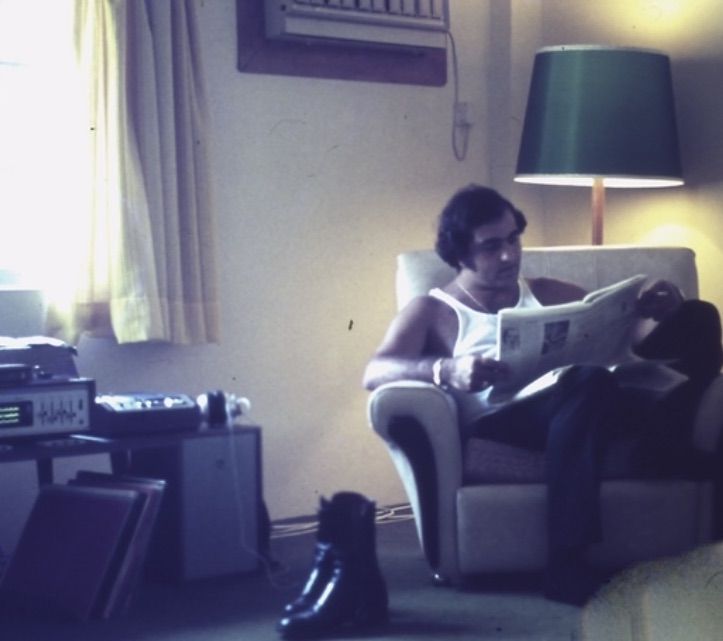

As soon as Eddie settled into his new base, my trips to Bahrain became a monthly routine that we all worked to respect. The preferred hotel for accommodating Beirut office visitors was The Gulf Hotel, being the most decent at the time, and due to its proximity to the agency. My personal visits were to ensure that Eddie had regular guidance as he started to receive Intermarkets’ global clients, not forgetting that my visits in many instances were in the company of my own clients, such as the Ceylon Tea Board executives. Eddie rented a ground-floor apartment in a residential complex called Al Moayyed Gardens, where many expat executives lived. After some time, the roots of one of the giant Banyan trees in his garden started to grow like a hill under his carpet in the main sitting room, and this became Bahrain’s most amusing joke amongst Eddie’s growing circle of friends.

During the time we spent together in Bahrain, Eddie was eager to share the story of his US education, which I later noticed he was eager to tell people he wanted to impress. It had all begun during one of his summer holidays in Beirut – at the time Eddie was still completing his secondary studies – where he met an American couple holidaying in Lebanon on one of the beaches. The wife chatted with Eddie and was impressed with his witty responses. She surprisingly suggested that the couple should offer Eddie the opportunity of an American university education at their own expense.

It took time to convince the Moutrans to let their son accompany the strange American couple to the US, but the intervention of wise relatives and friends allowed Eddie to graduate with a Bachelor of Science degree from Southwest Missouri State in business and marketing. Although Intermarkets had opened a branch in Bahrain to primarily serve its multinational clients, Eddie felt that to grow his new agency he had to secure market acceptance on par with the two leading agencies in the market. One of them was Fortune Promoseven, the agency established by Akram Miknass, who had moved his operation from Dubai to Bahrain in 1978. Miknass partnered with Jameel Wafa, who was the partner of His Excellency Sheikh Khalifa Bin Salman Al Khalifa, the Prime Minister of Bahrain, in the well-known travel agency, Unitag. Both Wafa and Miknass were granted Bahraini nationality, which opened a lot of doors for their agency. Moutran also felt a need to turn Intermarkets Bahrain into a homegrown brand like Gulf Public Relations, which was the agency founded by two Bahrainis in 1974, namely Khamis Al Muqla and Abdelnaby Al Shoala, who was later named Bahrain’s Labour and Social Affairs Minister. Eddie’s American education made him a hands-on manager, and this is where he found an entry point into Bahrain’s inner circles, which he was keen to join. The first door that Eddie opened was the media door and here he developed close friendships with English language media publishers and senior editors, such as Gulf Daily News and The Daily Tribune, which were becoming more popular on the island than Akhbar Al Khaleej. He also joined the Rotary Club, which allowed him to rub shoulders with the Jashanmals, the Moayyeds and many other leading businessmen.

At the time, Bahrain was very much influenced by the UK. The males of the ruling family were all graduates of Sandhurst, which cast British court colors on the interiors of the ruling family’s palaces, the island’s police force, their uniforms and all military ceremonies and parades. Bahrain had consciously adapted the British conservative mentality. Streets and family dwellings were maintained with an old-fashioned look. Even their building names were inspired by the British system. Strangely enough, a large part of the island was cordoned off and kept out of circulation for civilian traffic as it housed a large American naval base, but the Americans did not seem to have the same level of influence. Luckily, all the American brands that we handled were controlled from their UK offices.

Before long, Intermarkets Bahrain developed into the launchpad for the group’s expansion into the entire Lower Gulf region.

Related Chapters…

-

Chapter 54\ Then came the time to move to Bahrain

The multinational clients who were with MEMAS before the establishment of Intermarkets realized the opportunities posed by…

-

Chapter 55\ Due to the security situation, Intermarkets has moved to Bahrain

Staying at the Phoenicia Hotel, Samir Fares was the only link with our non-Lebanese clients. This meant…