I was personally assigned to handle this new account in addition to my responsibility towards Shell. Here, too, the close relation that I was lucky to groom with a well-travelled and highly professional client turned out to be like a new class in international business. One that I was privileged to take at the university of the practical world.

The first few meetings at the Ceylon Tea Board were spent listening and note-taking. These were the briefing sessions on which most of our work in the following years would be built. Then, as the proverb “charity begins at home” goes, both client and agency came to the spontaneous decision that, since most of our time was being spent in Beirut, promoting Ceylon Tea amongst the Lebanese public ought to become a priority. Even though there were much more important market challenges on T.G.’s list that required his more urgent attention.

Tea for the Lebanese was a medicinal drink, only taken if someone was down with a cold or flu. This hot drink was served to family members with stomach and tummy problems as well. The only tea drinking pockets in the country were Ras Beirut – particularly the area around the AUB – and all the Lebanese cities and villages that had a British missionary presence, such as Abey, Ain Zhalta, Miniara, Baalbek and Tyre. The missionaries who had settled in Lebanon to run the schools passed on the afternoon tea drinking ritual to the homes and families of their students. As we began brainstorming to come up with a solution to the Lebanese challenge, we stopped more than once to ask ourselves whether it was possible to change the perception of tea as a health treatment to a welcoming hospitality drink in an environment dominated by coffee.

Putting our challenge in its historical context, one needs to keep in mind that our task of making Ceylon Tea a popular drink in Lebanon was being attempted well before Lipton, Brooke Bond and Twinings were seen on the shelves of Beirut supermarkets.

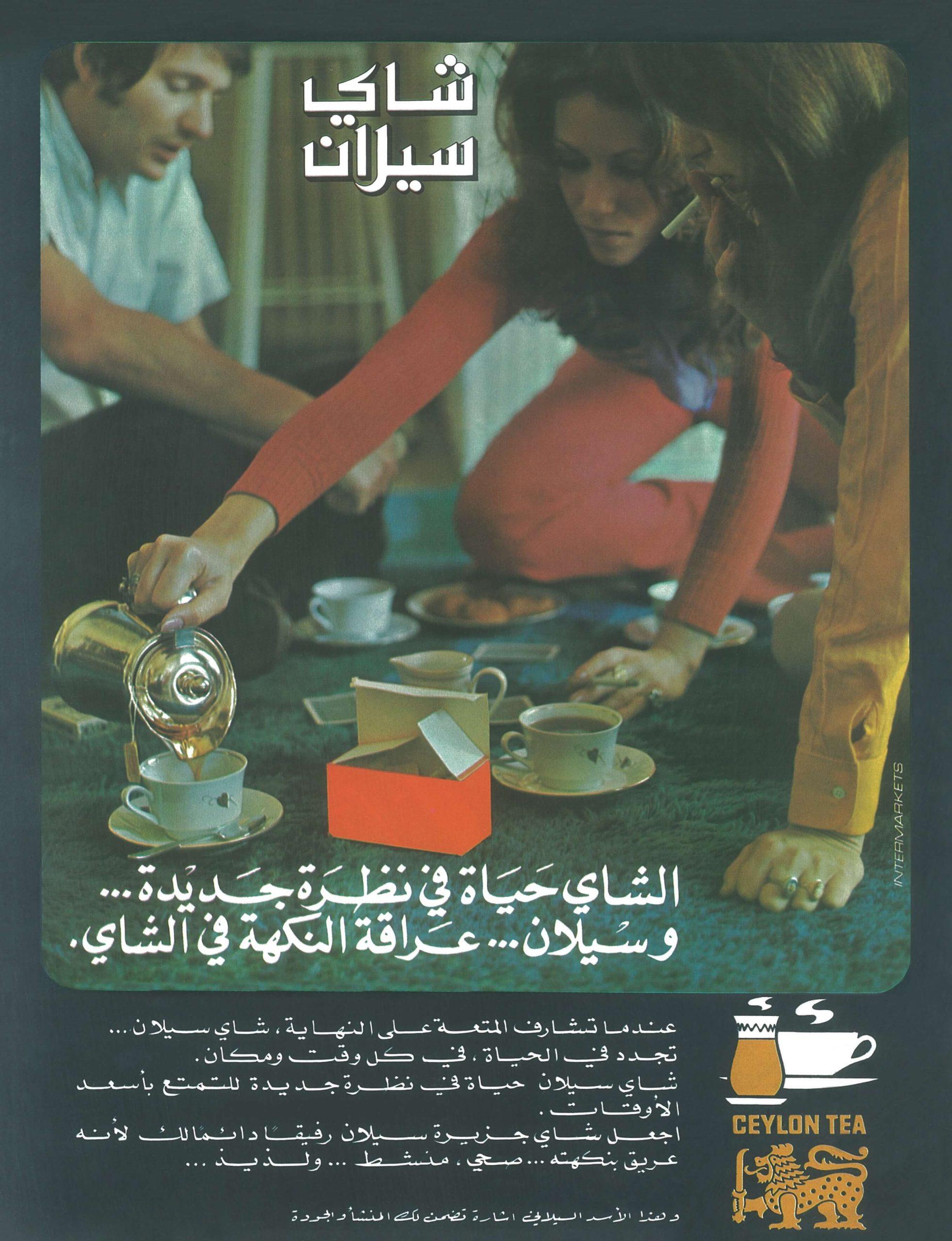

The account team at HIMA embarked on the task of developing a branding device to help buyers identify the teas we were encouraging them to drink, irrespective of whether these were taken out of cardboard packs, wooden chests, or jute bags for bulk tea buyers. Soon we were informed that the Ceylon Tea Board had recently introduced a global logo. This international branding device was introduced in 1972 and featured a spotted lion carrying a sword, which was borrowed from Sri Lanka’s coat of arms. The lion was perched on a base that carried the slogan “Ceylon Tea Symbol of Quality”. As this logo was meant for use on packs that contained pure Ceylon Tea only, T.G. briefed us to use it in all the Arab markets, and this is how it became the cornerstone of all our marketing and support activities.

To get the ball rolling, the agency was introduced to the tea importers whose shops were in Fauche and Marseillaise streets. There, we met Ludwig Tamari, a Palestinian merchant who had settled in Lebanon after 1948 and continued the family business that had been extremely successful back at home. Tamari was a tea expert, as in Palestine tea was the more popular hot drink, thanks to the influence of the British Mandate on the country. Tamari realized the opportunity of cooperating with the Ceylon Tea Board, so he agreed to carry the sworded lion emblem on his “Horse Tea” packs, and soon he became one of the most favored Ceylon Tea importers in Lebanon.

The first Lebanese merchant to join Ceylon Tea’s club was a large importer of provisions called Maurice Jabra. His Beirut shop was in Marseillaise Street as well, but his major base was in Zahlé at the center of trade with Syria and across the entire Beqaa Valley, where tea drinking was popular. Then another Lebanese grains and provisions trader came onboard by the name of Saeed Boubees, who had a tea brand registered under the name of “Boy Tea”, to whose pack he also added the sworded lion emblem after signing an agreement with T.G. to only import Ceylon Tea.

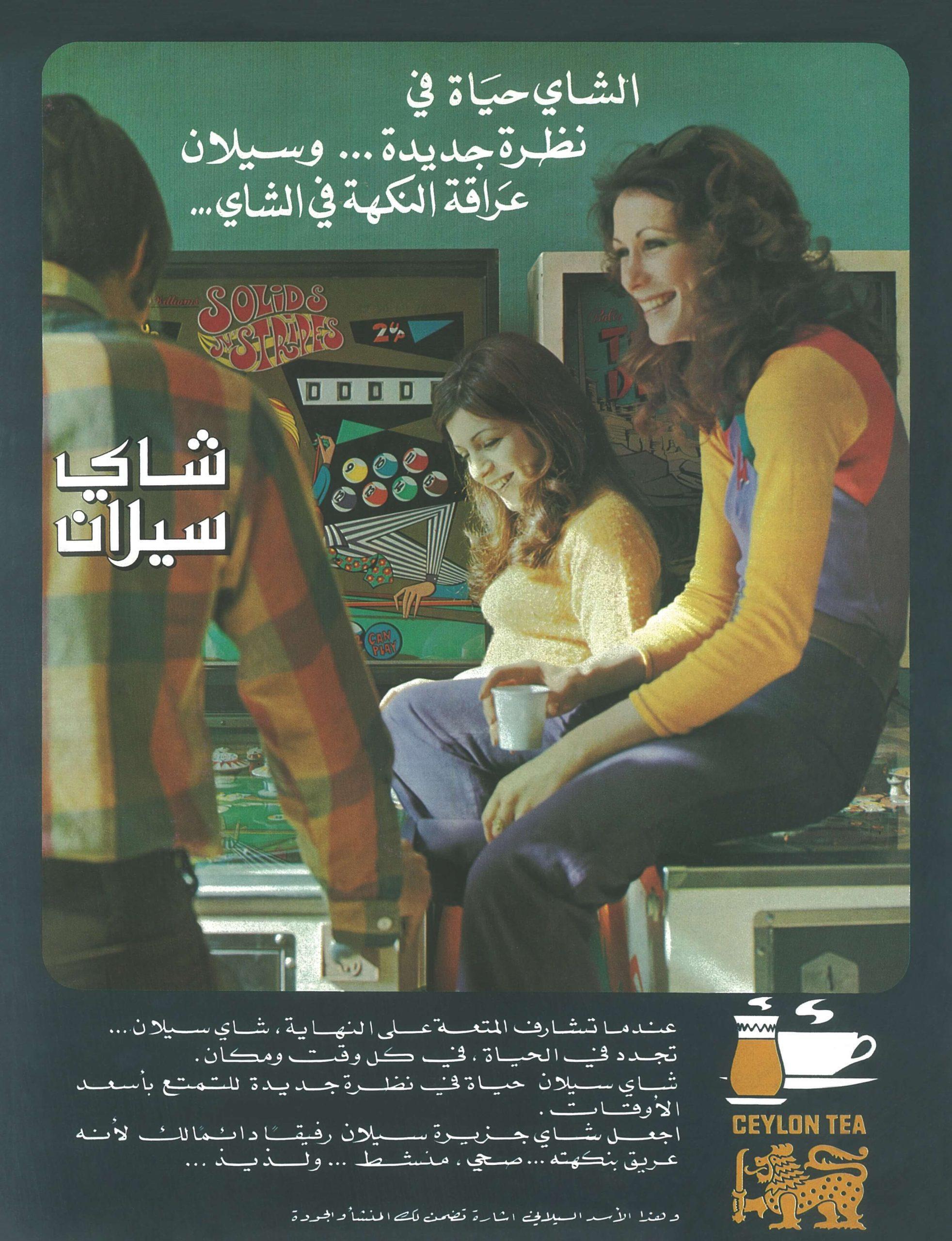

The advertising campaigns targeted the younger generation by featuring joyful gatherings, including house parties and arcade machine joints – two very popular gathering places at the time.

T.G. and I travelled together amongst the Arabian Gulf markets. We introduced the Ceylon Tea Board to the Baashen cousins in Saudi Arabia, who were the market leaders with their Abou Jabal and Abou Haram teas, which were sold mainly in bulk out of wooden chests that contained the dark thick tea leaves wrapped in aluminum foil. The old Baashen family head was so confident of his control over the tea market that, on our first visit, he said that even if he put dirt in the wooden chests that carried his red triangle, the Saudis would continue to buy it.

We also met the Basamhs in Gabel Street, at the center of old Jeddah, and there we were told that most of the Saudi business was controlled by the Hadhramauti (from Hadhramaut in South Yemen) merchants who had immigrated and settled in Jeddah. We were also told that all family names (surnames) that started with a “Ba”, like Baashen, Basamh, Badreeg, Bakhshan, Banaja, Bakhashab and Bawazir, were of Hadhramauti origin.

We travelled to the UAE, whose tea trade was comparatively small because Indians were in control of the food and provisions market, hence their preference was obviously for Indian tea.

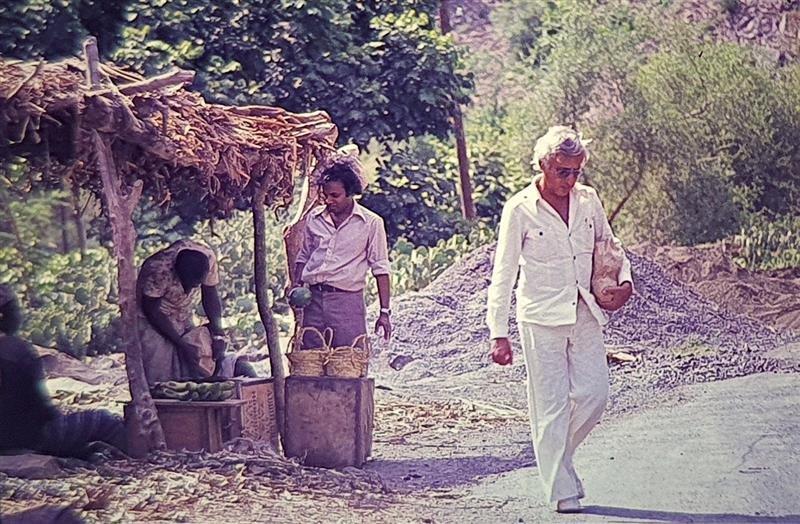

After Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Sharjah we travelled to Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. Some of these market visits were a first, like my trip to Yemen. We landed in Sanaa following a bumpy flight – due to the high altitude of the Yemeni capital – to be greeted by Nadim Hassan Ali, who ran his advertising agency, Hams, and travelled around the vast country for his employer, British American Tobacco. Nadim drove us to Taiz and Hodeida along the winding mountain road that had been recently completed by the Chinese, and we felt that we were going to be pushed over the dangerous cliffs by speedy drivers who were chewing qat.

At the end of the first visit, we went back to Sanaa, where Nadim’s wife, Aida, accompanied us on a tour amongst the tea trade, driving her Land Rover forcefully. Then, at the end of every day, she challenged us to a game of chess, where she was always the winner.

When T.G. Peiris felt I had been introduced to most of the markets and tea importers around Arabia, he arranged a trip to Sri Lanka for me, to complete my tea education. Luckily, in the meantime, Raymond Hanna had worked on enhancing his contacts within the Ceylon Tea Board and thus became a close friend to some of the more influential members. So, when it came to planning my first visit to the island, one of his newly made friends – who was also a senior member of the Sri Lanka Tourist Board – assigned his people to plan my stay.

Related Chapters…

-

Chapter 123\ Who is sleeping in my bed?!!

In July 1995, Intermarkets won the Rothmans account, having pitched against Publi Graphics, Oster-ads, and Team Advertising.…

-

Chapter 31\ A Ceylon Tea caravan through Arabia

I was personally assigned to handle this new account in addition to my responsibility towards Shell. Here,…

-

Chapter 85\ Shredding QAT Leaves with Moulinex

The Dubai agency continued to grow and attract people from all around the Intermarkets network. Samir Fares,…