Most companies in Lebanon employ officers to run after government and banking formalities. At Publicite Universelle, there was a young and pleasant man called Saadeh Abou Chakra, who was called “Mr. Fix It” by all the staff. Saadeh commuted from the Chouf village of Baakline every day. In other words, Saadeh was an authentic Lebanese villager who had been modernized by his job. Saadeh had earned his title because he had a solution to every problem.

At Publicite Universelle, the agency had to face – almost daily – the challenge of securing censorship cards for the advertising films that were due to run on the cinema screens it represented. These were obtained from the Lebanese General Security. One day, Saadeh had to take one of the agency partners’ cars to the Traffic Authority for what is commonly known in Lebanon as the ”mechanique”. There, he bumped into an old friend of his who was in the process of applying for a touring license for 20 Volkswagen vans. The large number of vehicles alerted Saadeh to a new business opportunity. He casually questioned his friend and discovered that a new fruit juice brand was to be launched soon. Saadeh rushed back and excitedly announced that he had identified a promising new client.

A few days later, we met with the man behind this fleet of delivery vans, a Syrian businessman called Rateb Krayyem. Krayyem was one of several Syrian industrialists who were in the process of moving their operations from Damascus to Beirut, due to new tax laws that were being introduced and increased government controls back at home. Rateb Krayyem turned out to be an expert in manufacturing fruit juices and a cultured person who had loved Lebanon since his childhood. Therefore, he did not need a great deal of reasons to immigrate. Soon after his arrival, he bought a large plot of land on the outskirts of Beirut and immediately started building a state-of-the-art factory. He also bought a luxurious apartment in Ain Saadeh that gave him a panoramic view of Beirut, and it was there that a lot of our early meetings were held. If our meeting happened to take place after a stormy night, the chances were that Krayyem would share with us – in a vivid, cinematic way – the scenes of thunder and lightning that had kept him up until the early hours of the morning with a glass of cognac in his hand.

After a great deal of brainstorming, we jointly agreed to call the new brand “Freshy” – a name that Krayyem had suggested at our first meeting, but which we only endorsed after checking to see if such a name existed in the authorities’ brand registry. Accordingly, we returned to the agency loaded with excitement over the prospects of developing a dynamic launch. By that time, Publicite Universelle’s business had expanded, and a new creative director had been hired. He was another Armenian, who had graduated from the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts (ENSBA) in Paris and had undertaken an internship at Dupuis Compton (an agency that was later acquired by Saatchi & Saatchi in its aggressive bid to secure a larger share of the Procter & Gamble business).

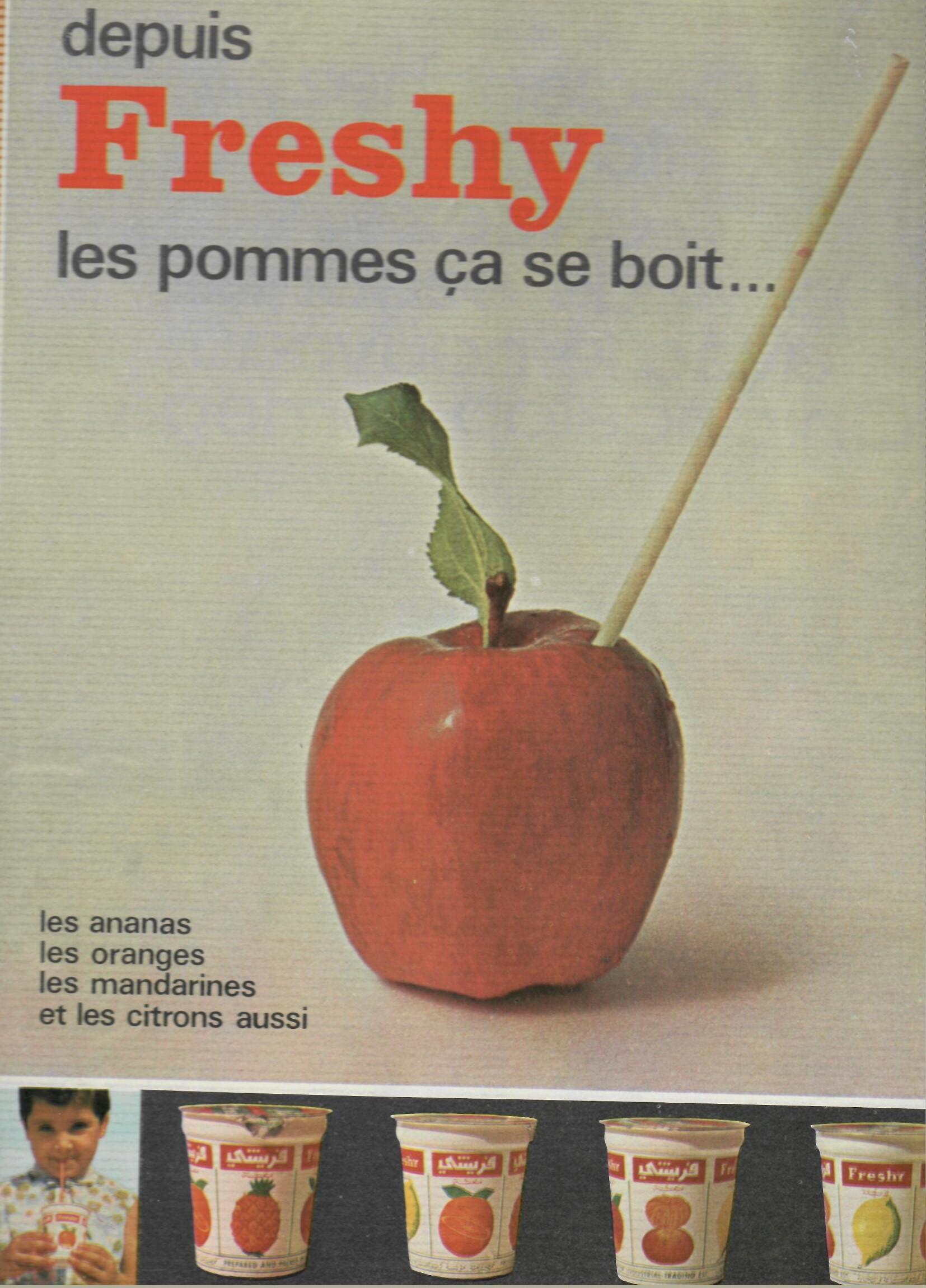

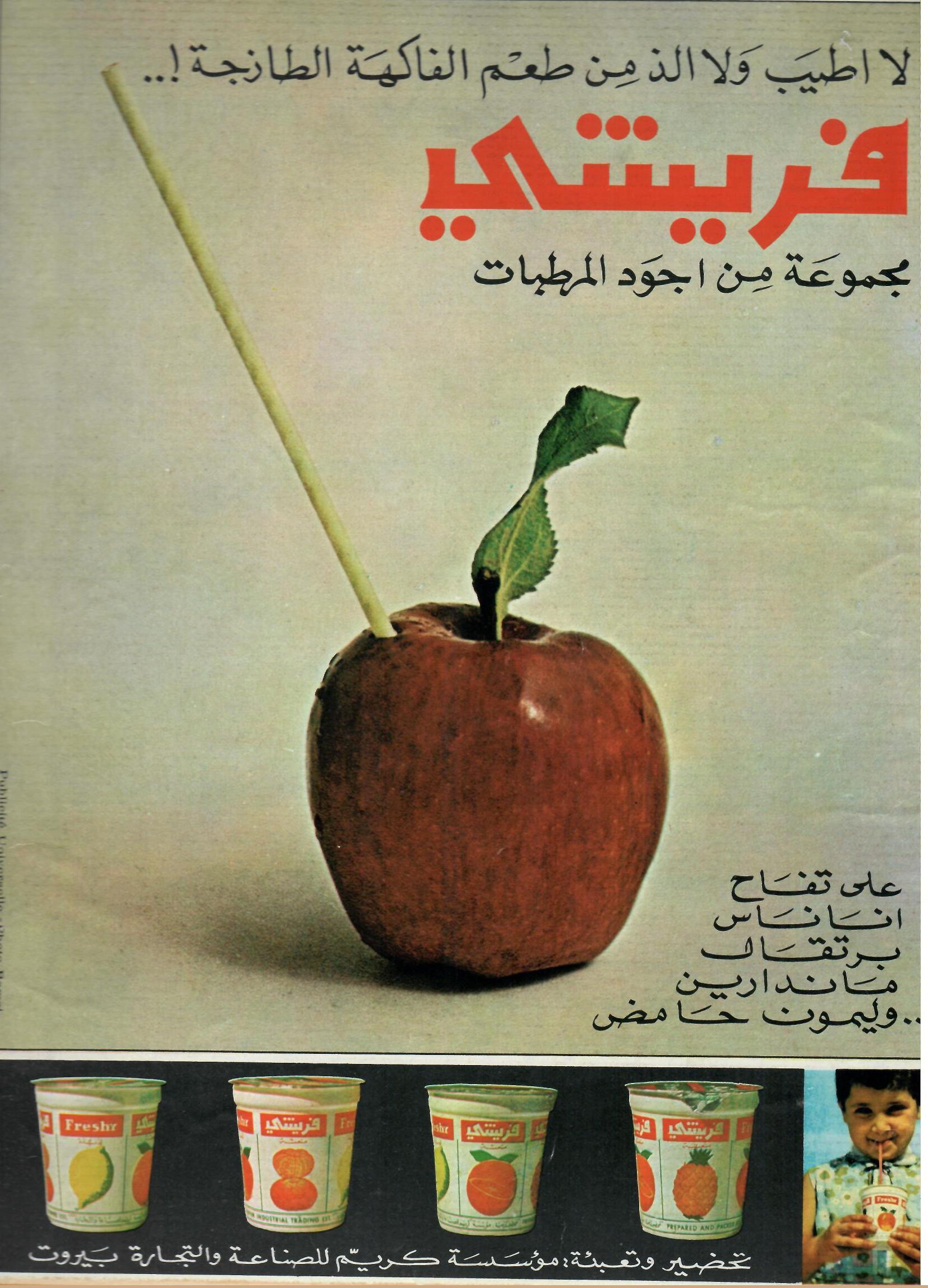

The brief was to introduce Freshy to the Lebanese public as the fruit drink that was closest to natural fruit juice, keeping in mind that consumer protection authorities were not active in Lebanon at the time. The French-educated creative director scribbled a headline – “Depuis Freshy les pommes ca se boit” – which I adapted to Arabic and English. It read: “Now with Freshy, you can drink the apple.” Having agreed on the headlines, together we arrived at the idea of a print ad that featured an apple, orange or a pear pierced with a drinking straw, which would be capped with the above headline. The body copy would introduce the product and the full range of flavors.

We launched in spring and Freshy became the most popular drink that summer. We did not want the momentum to slow down with the changing weather in Lebanon, so we developed a second campaign for autumn and winter, which said: “Freshy refreshes you in winter the same way it does in spring and summer.”

Locally manufactured FMCG brands could afford neither a budget to produce a TV commercial, nor enough money to support an adequate TV launch. Press continued to be more affordable and Publicite Universelle’s clients were easily lured into the discounted page rates that always seemed to be on offer.

At the agency’s Christmas party, Saadeh collected an envelope containing a fat cash gift in appreciation of his alertness and commitment. At the same time, all of us had acquired a new lesson, which we applied at Publicite Universelle. New business was the responsibility of each one of us, from the agency’s marketing officer to the bookkeeper and the receptionist.