My career progression was in fast-track mode at Publicite Universelle – hard work and sheer dedication, as my boss put it. As a next step, Philippe Hitti justified my eligibility for the role of general manager by convincing his partner Elie Nawar that I was respected by the agency’s clients, had demonstrated my ability as an efficient Jack of all trades, and was the only English-speaking university graduate amongst the agency staff. This position had never existed before, as management responsibilities were split between the two partners. Philippe succeeded and I became the general manager of Publicite Universelle in early 1970. By that time, cooperation with Geadah Brothers had progressed due to the improved results we had delivered on General Foods. Soon the agency received a brief for a new brand from its rich portfolio, namely Uncle Ben’s rice. At a time when Lebanese housewives were only using Egyptian rice, Uncle Ben’s offered the luxury of choice – an American parboiled long grain rice product marketed out of Houston, Texas.

Since 1946, Uncle Ben’s products had been sold in packs carrying the image of an elderly African American with a bow tie; an individual believed to be a rice grower who supplied rice to the American army during World War Two, and who chose the name “Uncle Ben” to expand his marketing efforts to the public. Obviously, neither the thought of a different type of rice nor the brand story were of relevance to Lebanese housewives, who had learned how to cook rice from their mothers for many generations. Rice being a staple diet of Lebanese families, the different taste was another serious challenge for the brand we were tasked to promote. When we received a pack containing examples of Uncle Ben’s American advertising material, we all agreed that none of its ads could be used for the launch in Lebanon. The objectives of the campaign we needed to develop were at odds with the campaigns sent from the US, which were designed to advertise an established brand and product rather than introduce a new one.

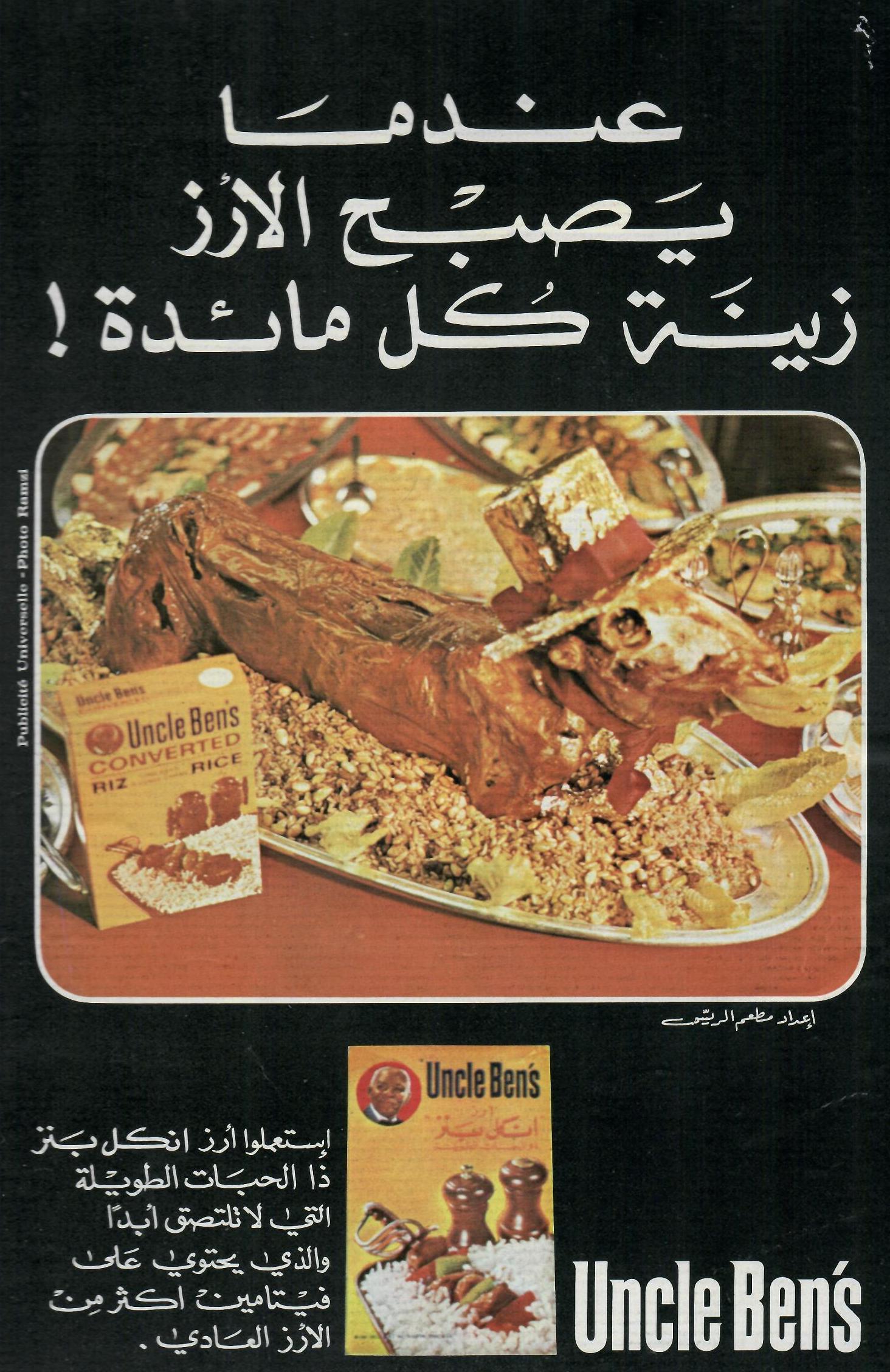

The agency’s brainstorming led to the creation of a campaign idea that proved American long grain rice was as tasty in popular Lebanese recipes as the rice traditionally used for cooking. The headline read: WHEN RICE BECOMES THE CROWN OF EVERY BANQUET. Publicite Universelle approached well-known Lebanese chefs and restaurants, commissioning them to cook their signature dishes using Uncle Ben’s rice. All the photography had to be done in busy kitchens, which proved to be a tough challenge, as I handled the photography without the assistance of either a home economist, lighting equipment, or technicians to add depth to the many-layered dishes. Still, each of these sessions was a memorable experience, and more of the agency’s staff began to offer help in the hope of tasting the delicious dishes.

In the late 1960s, advertising agencies in Lebanon raced to conclude exclusive deals with the different media groups, hoping to secure additional profits and advertising space or time for their clients at discounted rates. In addition to the many contracts that Publicite Universelle had with the different cinema theatres, Philippe wrapped up an exclusive deal with the publisher of Alf Laila W Laila (1001 Nights) magazine. This magazine was referred to as the Arabic Playboy, since it was the only magazine in the region that was dedicated to nudist photography. This breach in Lebanon’s code of publishing ethics seemed to have been made possible by the fact that the magazine’s publisher was the head of the Lebanese journalists’ union, Melhem Karam. The agency made sure that this newly contracted magazine received the lion’s share of Uncle Ben’s first media plan. This was easily approved by the local distributors, who were happy with the discounted ad rate featured on its media plan. The campaign ran and – at the Lebanese end – all seemed to be very happy. However, one day we were informed by Geadah Brothers that Uncle Ben’s export director was due to visit Lebanon, and the agency needed to prepare for his visit.

Ben Baldwin was a pleasant American export director who was happy with the way Geadah Brothers managed to place his brand on the shelves of all Beirut’s appropriate outlets. He was also happy with the repeat sales to most of the groceries in the Ras Beirut area surrounding AUB and the Beirut College for Women. He much enjoyed the Lebanese hospitality, particularly the evening that Geadah Brothers hosted at La Salle des Ambassadeurs at Casino du Liban. Ben finally visited the agency, where one of the owners and the newly promoted general manager took him through every step of the launch campaign for his flagship rice, of which we were proud. He complimented the campaign idea and the many executions for print, point-of-sale, and the collateral we had created. He then grabbed a copy of Alf Laila W Laila from the pile we had displayed on the conference table, flipped through the pages, and stopped to look at the ravishing center spread. Then he turned to us and coldly asked: “Could any one of you gentlemen tell me why we are using a magazine that only shows naked women to advertise Uncle Ben’s rice, which mainly targets housewives?”

It needs to be remembered that I had the additional role of acting as the translator at this meeting and my boss turned to me and whispered, in typical witty Philippe Hitti fashion: “Tell him that our research shows that Lebanese housewives are the main readers of this magazine.” Ben Baldwin travelled back to Houston with an answer he pretended to have accepted out of courtesy to his distributors and their advertising agency. But until this day, I remain convinced that this seasoned and polite American avoided telling us that he was not so naïve as to believe what we’d said, nor did he want to create further embarrassment by questioning why this magazine was placed on Uncle Ben’s media plan in the first place.