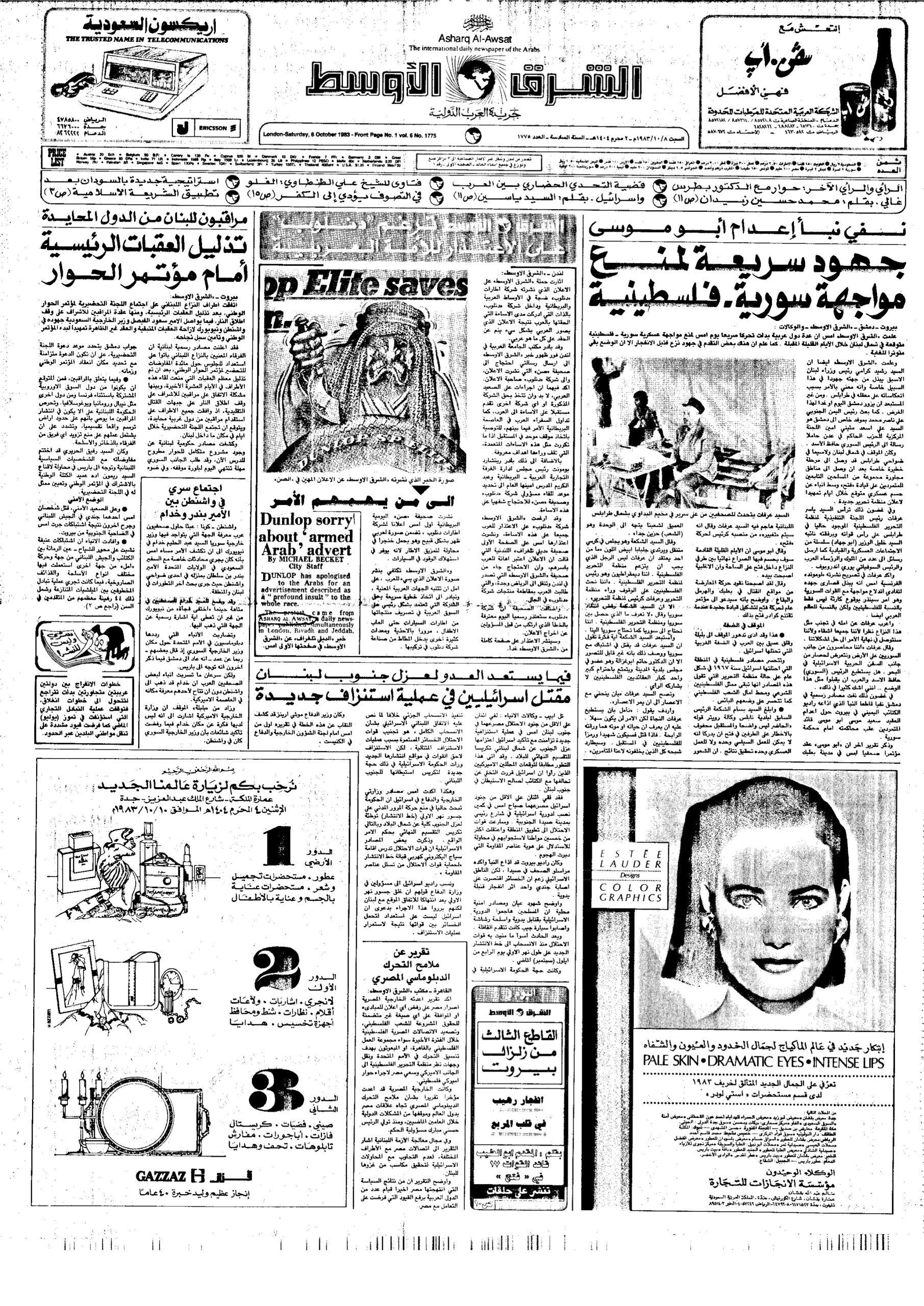

In 1978, Dunlop introduced a new tire that was meant to have a better grip on the road and accordingly reduce petrol consumption. For the launch, Dunlop’s agency, Saatchi & Saatchi, prepared an advertising campaign that ran in the British daily press. It featured J.R. Ewing, the popular hero of the highest-rated TV soap opera “Dallas”, pointing his pistol at the tire and saying: “You wouldn’t want that now, would you?” The next day, the campaign featured a hawk-nosed grinning Gulf Arab in national dress, brandishing a curved Omani dagger at the Dunlop tire, while saying the same statement as J.R.

On 4 July that year, two Saudi brothers named Hisham, and Mohammad Ali Hafiz launched an Arabic language international newspaper in London, which was a pioneer of the “offshore” model in the Arabic press. It became instantly popular with its distinct, green-tinted paper. Asharq Al-Awsat reproduced the Dunlop ad featuring the Gulf Arab on its front page, and the doors of hell instantly opened in the Arab world. The Saudi Ministry of Defense had a huge contract with Dunlop to supply tires for its army vehicles. This was cancelled and the British foreign secretary had to fly to the kingdom to apologize for the advertisement on behalf his government and lobby to have the Dunlop contract re-instated. This request was rejected, resulting in Saatchi & Saatchi losing the lucrative Dunlop business.

Between 1982 and 1991, Saatchi & Saatchi operated in the Middle East via the affiliation it had established with Intermarkets to service British Airways. Following those nine years it retrenched its independent Middle East business under the leadership of Salim Barakat. Then in March 2010, it established its own presence in the Middle East, which was regionally managed from Dubai, except for Lebanon, where the management duo – of its affiliate agency – insisted on the autonomous management of the Beirut agency. This was named Saatchi & Saatchi BD&A, under the pretext that its local market had its own peculiarities[1] .

In February 2011, I was on a business trip in Oman when I accidentally bumped into Fouad Kouraytem, an old P&G client who used to be the general manager for Saudi Arabia. To my great surprise, I discovered that Kouraytem was furious because he blamed me for having introduced to P&G the two gentlemen who have become their current agency partners in Lebanon during the period that Intermarkets was its agency of record in the Arab markets. He continued to explain that when P&G realized that the film production charges that it had been receiving from Saatchi & Saatchi in Lebanon were much higher than it had ever paid anywhere, it forced a sudden audit of the preferred production company’s accounts. This revealed a massive rip-off from the agency, which resulted in a sternly worded ultimatum to Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide demanding an immediate rectification of the Lebanon blunder at the expense of losing all P&G’s business around the world.

The Lebanon management team were immediately fired. Saatchi paid back to P&G the totality of the overcharged money, and the Lebanon account was brought back under the Saatchi Dubai team. The fired duo established a new agency, which they named Quantum, announcing to the Lebanese market that they had done so because they had stopped seeing eye-to-eye with their international partners, whom they had been glorifying up until a month earlier. They arranged a quick fix by tying up with M&C Saatchi and launching a campaign that said: “New Name, Same Agency, You No Longer Have to Say It Twice.”

At the Dubai Lynx advertising festival in 2009, Fortune Promoseven in Doha was stripped of its Agency of the Year title and most of the awards it had received. The credibility of the awards suffered, and the agency’s reputation was tarnished. This led to the restructuring of the FP7 Group and its rebranding as MCN[2].

After having been one of the first global agencies to set up shop in the Middle East, Y&R committed a major mistake when Colgate-Palmolive appointed the agency to handle its business in the MENA region. It summoned an ageing Dutch executive back from retirement and entrusted him with setting up a network of its own in Arabia. Tiemen Bosman stepped out of the icebox where he had been living and travelled to Tel Aviv, where he spent six months working on setting up Y&R’s MENA head office, totally ignorant of the fact that the Arabs and Israel had been in a state of war since 1948, and consequently had no business or any other type of relations.

Then Y&R, in what seemed to be an afterthought by Bosman, bought Team Advertising, convinced that this agency was physically present in all the MENA markets where Colgate-Palmolive needed to be serviced. It soon realized that this was not true. The surprises did not stop there. The two Lebanese partners entered a head-on conflict led to court cases which where only concluded when WPP stepped in.

Looking back at these few examples, one wonders why global experts who claim to know it all, continue to tread in dark alleys, simply due to a blinding lack of trust.

[1] Lebanon Communicating – Page 175

[2] Campaign Middle East – Issue of the 7th of November 2010