During my time at AUB, Lebanon was known as the “Switzerland of the Middle East”. In the harsh climate of the region, Lebanon enjoyed four distinct seasons, with autumns colored by fallen leaves, rainy and snowy winters, followed by blooming springs, then the joyous summers when Lebanon’s natural beauty was worshipped by the hundreds of Gulf families who ran away from the humidity and heat at home.

Lebanon not only offered its natural beauty to visitors, but it also flew them in on MEA, the Lebanese national carrier, and the best Arab airline of the time. It offered them entertainment options matched only in Las Vegas and Paris, the jewel in its crown being the world-famous Casino du Liban, with Ella Fitzgerald and Charles Aznavour on its stage and Charlie Henches’ spectacular shows “Mais Oui” and “Hello” entertaining the crowds. Meanwhile, on the stairs of the Temple of Jupiter, Fairuz and Oum Kalthoum made thousands of Arabs break the record for standing ovations throughout the days of the Baalbek International Festival.

Lebanon had clean and tidy beaches that attracted European sun lovers, while its restaurants, arak and wine were continuously quoted in international culinary guides.

The summer period brought joy to my heart following the two fall semesters at AUB. I made the best of my hometown, Aley, and its status as a leading Arab resort. Aley’s population multiplied during the summer as Beirut’s citizens who owned or rented summer houses rushed to spend the months of June, July and August making the most of its pleasant weather and joyful atmosphere.

My summers in Aley were a mix of work and pleasure. The good parts of the day – my mornings and early evenings – were spent helping at Pharmacy Baroody, my father’s pharmacy, while the rest was spent walking up and down Aley’s crowded high street with friends, invariably ending up at one of the street-side cafes. Aley used to be a melting pot of Gulf Arabs, to the extent that the entire Kuwaiti Government spent its summers there. Even the country’s state laws and decrees were frequently headed “Aley”, followed by the date.

At the pharmacy, I came to realize that consumerism in Kuwait was advanced compared with other Arab countries, even my own arrogant Lebanon. The Kuwaitis often came in asking for toiletries, cosmetics and medicines that were unknown in Lebanon at that time. My father had to search for the agents of these brands and then order them, just so he could keep his clients happy. The Qataris had their summer palaces in Aley, too, but they seemed to be the learners here. A friend of mine, Fouad Joujou, who had just established a film production company, was commissioned that winter to film the palace of the ruler of Qatar under the snow, in return for a very handsome fee.

Watching our Gulf Arab visitors at the time was an opportunity to prepare oneself for a future largely dependent on riding the wave of pan-Arab/regional business. Gulf Arabs were loyal Virginia tobacco smokers and accordingly all shops stocked Rothmans, Dunhill, Craven A, and State Express, which were alien brands to the Lebanese. However, as the red Marlboro pack was so flagrantly seen in the breast pockets of trendy Lebanese youngsters, many Gulf men returned to Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain with cartons of this new brand. Gradually the switch to American tobacco crept into one Gulf state after the other. The same with toiletries, cosmetics, food, and dress.

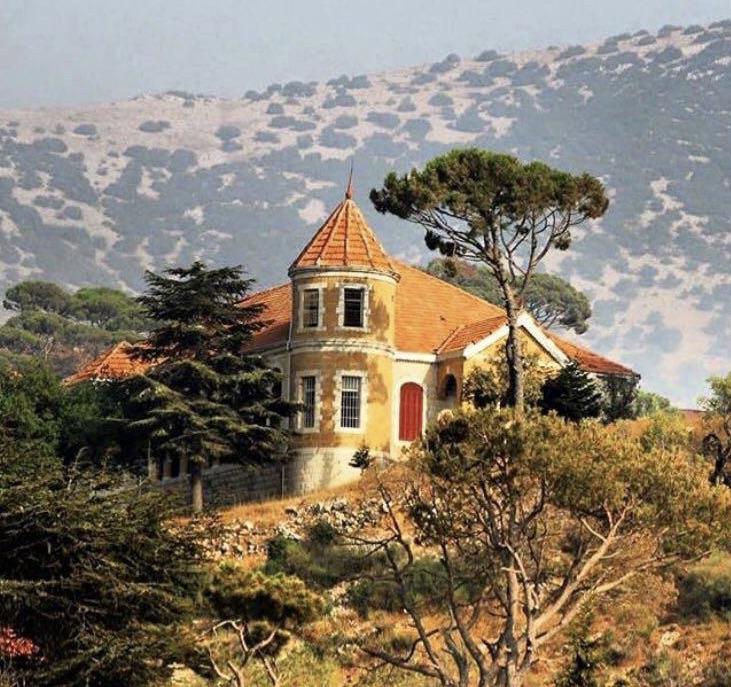

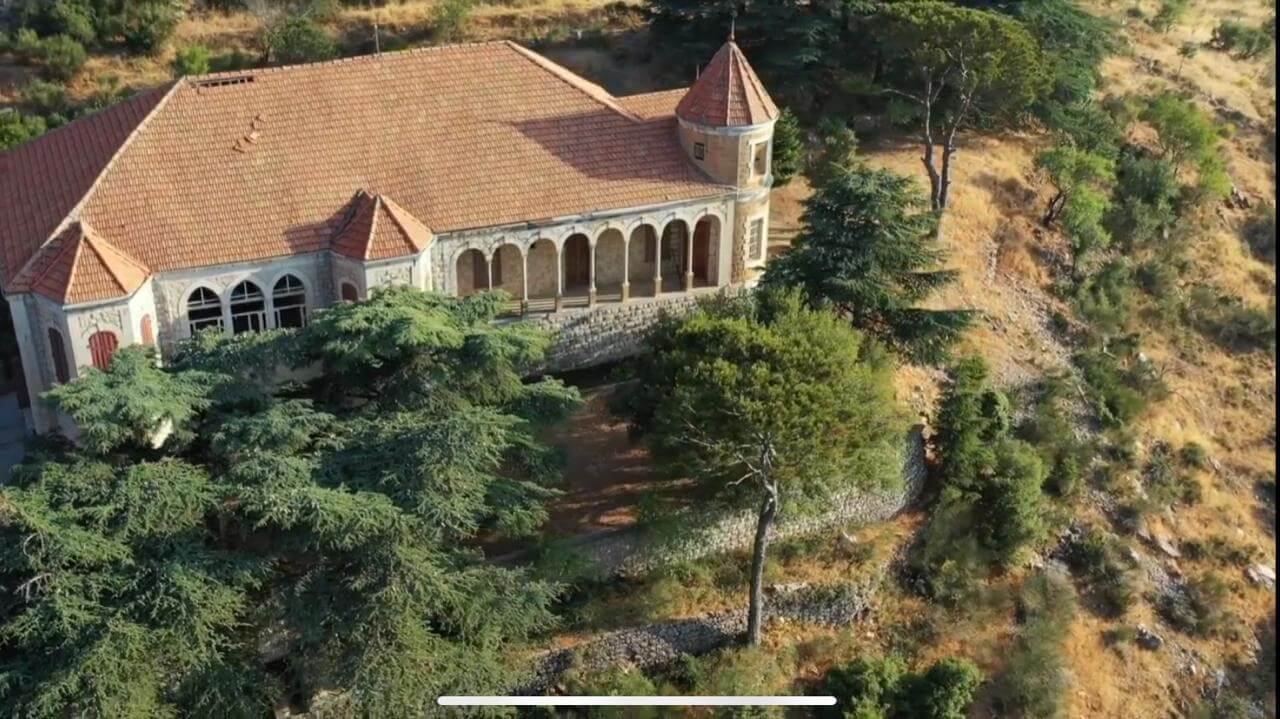

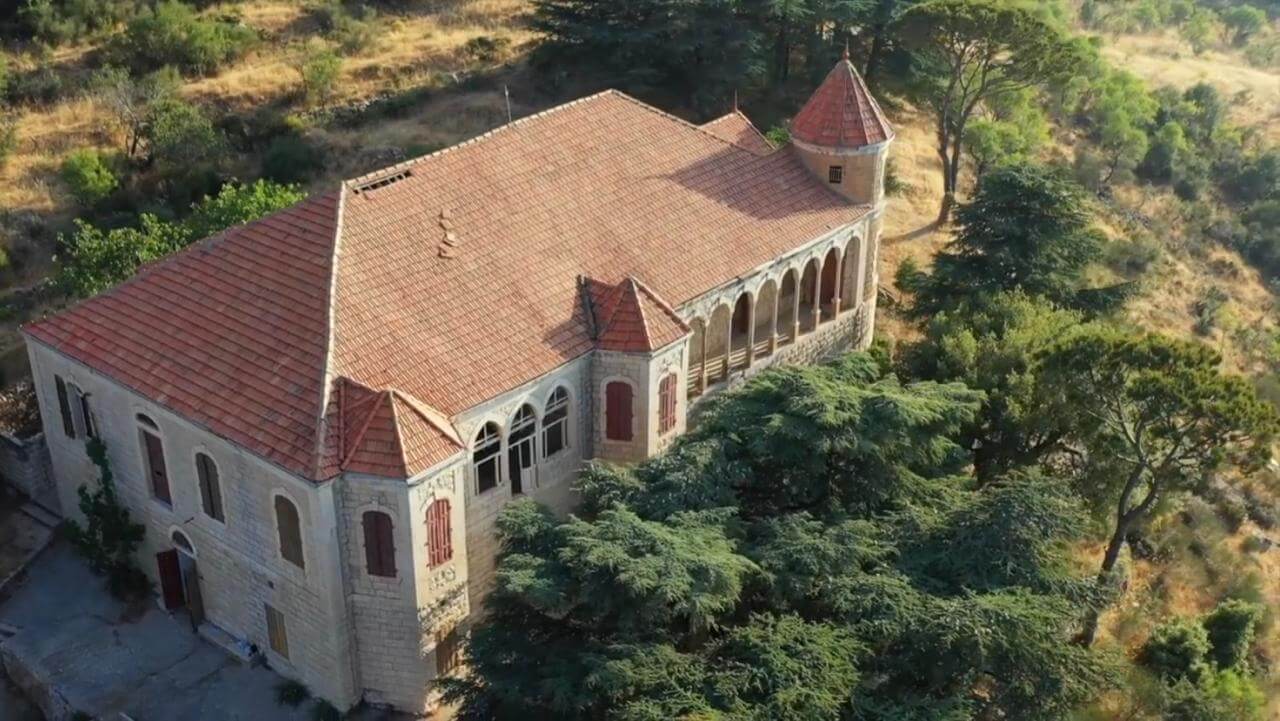

The summers were my opportunity to spend time with my grandparents in Ain Zhalta and Zahlé. There I experienced firsthand the importance of family values and traditions. My summers in Ain Zhalta were spent at Dar Al Toufic, the Raad’s ancestral home, which is perched on top of the hill that crowns this lovely village.

Later, when I read David Ogilvy’s biography, I thought if Ogilvy were an Arab, he might have traded Dar Al Toufic for his Chateau de Touffou.

Ain Zhalta during my summer holidays became the base camp for wonderful hikes amongst the natural beauty of the Chouf Region, including the climbing of Ain Zhalta’s cedar mountain, which was later made a nature reserve. We would climb the spectacular peak, which made me, and my hiking companions feel so close to God. The panoramic view from the peak was breathtaking, as we were able to see the whole Chouf region and the entire Beqaa Valley, including Lake Qaraoun.

Our descent to Ammiq on the Beqaa side of the mountain, through the oak tree forest with its squirrels, partridges, foxes, and porcupines, were memorable journeys that helped us discover the natural beauty of the Lebanese mountains. So vivid in my mind is the hike when we were woken by the howling of dogs leading a group of Beqaa Plain gypsies (Nawar) attracted by our still struggling campfire. The gypsies were hunting porcupines, which they skinned at our camp and insisted on inviting us to sample the delicate meat. In later days, when I started learning the art of storytelling, one of my colleagues observed that most of my stories had mountains as their backdrop.

My summers in Zahlé were as fascinating, since every day after taking my turn helping my grandfather at his pharmacy, I spent the late afternoons walking to the only bookshop in the city, where I would buy a war story paperback and begin reading it at one of the Berdawni River cafes. My grandparents lived in a part of Zahlé called Al Mouaalaka, which overlooked the Beqaa. We often slept in the open on the wide balcony, where every day the whistle of the train approaching Zahlé’s station woke us. Soon afterwards, visitors from neighboring villages on their way to Zahlé, the uncrowned capital of the Beqaa, would drop by carrying gifts of produce and fruit, as my grandfather was well known for his care of the sick and the elderly. Staying with my two grandparents for a few weeks each summer was an extension of my education, as there I learnt honesty, humility, respect for senior citizens, and love for Lebanon.

Those weeks with my grandparents were always concluded by a return to Aley, where I would get ready to go back to university and assist my Mum and Dad in getting ready for the fall. What was nice about living on the ground floor of a four-story building was the fact that my uncles and their families spent their summers on the other three floors. The entire clan would get together for morning coffee around the fishpond facing the common garden entrance.

During those morning chats a lot of the family’s plans were agreed on and finalized, and our problems and challenges were also faced. So, on one of those days, I announced my wish to start working, and all around the pond seemed dumbstruck. They thought I wanted to drop out of university and get a full-time job. However, I explained that my plan was to line up the courses I wanted to take on certain days, and even in morning blocks, which would give me the opportunity to get a paid part-time job that would allow me to reduce the huge amounts of money my father was paying. Suggestions from my family poured in instantly, but none of them satisfied my dreams.

Soon the family elders noticed that I was shying away from any job related to pharmacy. At that moment, my uncle, a businessman and the owner of a large trading organization, suggested I contact one of the company’s banks and ask if they could take me on as an intern. To everybody’s surprise, I thanked my uncle, announcing that I was not interested in banking, and pleaded with him to help me find a job with an advertising agency instead.

Our coffee session that morning was extended, as all the family members who were there wanted to know what it meant to work in an advertising agency, and why I wanted to ditch my father’s pharmacy and go into this strange profession.

As expected, this same uncle stepped in to remind them that his trading organization – Baroody Brothers & Company – had thrived because of ad campaigns that had helped launch new product concepts into the Lebanese market, and whose Arabic language advertising slogans had become part of the nation’s vocabulary. It was not fair to leave my Uncle Emile on his own to defend the profession, so I stepped in to highlight my fascination with what my friend Rafic’s uncle, Assaad Al Najjar, had achieved in launching the first Arabic keyboard typewriter to the market. And how he had been successful in introducing the concept of photocopying and safes for home use because of his pioneering editorial campaigns.

All these experiences I had picked up from visiting Najjar Continental in Weygand Street in the company of Rafic and listening to his father tell us the company’s success stories.

A week later, I was reading a report about the advertising industry in Lebanon in An Nahar’s weekly supplement while on my way to an interview with Philippe Hitti, the co-owner and CEO of Publicite Universelle, the advertising agency employed by Baroody Brothers & Company, and a very close friend of Uncle Emile.