One of the major HIMA accounts to move to Intermarkets was the US-made white goods firm Westinghouse. Their export director was a charming middle-aged American called Harvey Morse Jr. with whom I established a close relationship in record time, as this was easily pegged to our mutual professional respect, particularly since Harvey was new to the region.

The most important market for Westinghouse in the Middle East was Saudi Arabia, and Harvey was very keen to visit. Raymond Hanna, the agency’s lead on this portfolio, suggested that I accompany the client on his first visit. Contact was made with the Saudi distributor of Westinghouse, who welcomed the visit, even though it was taking place in the midst of the Muslim world’s fasting month of Ramadan. Raymond Hanna gave his client and me a comprehensive lecture on this third pillar of Islam. He warned us not to drink, eat or smoke in public before sunset. However, he failed to mention any thing about working hours in the Kingdom during the Holy Month.

We flew MEA out of Beirut and landed -around lunch time – at a very crowded Jeddah airport, which was in the middle of the city in those days. We fought to retrieve our suitcases from the loaded trolleys that had brought them from the aircraft and walked to the customs desk where the contents of our briefcases were searched.

Walking out of the arrival hall, we were welcomed by a short thin gentleman in a white thawb (gown) and a cap (aloussi) on his head, in stark contrast to the red and white headgear (hatta) that was worn by all the other men around us. The gentleman introduced himself as Saleh Balahwal, general manager of the Mahmoud Saleh Abbar Company, the agents of Westinghouse in the Kingdom. En route to the Jeddah Palace Hotel, Balahwal introduced himself as being of South Yemeni (Hadramauti) origin, although he had lived all his life in the Kingdom and consequently had been granted Saudi nationality. Saleh was softly spoken in his own version of the English language, to the extent that, strangely enough, he pronounced the letter “J” as a “G”, in the Egyptian way. As he was dropping us at the hotel, Saleh explained that Ramadan working hours in Jeddah were 10am to 4pm. Then they resumed work at 8pm, after having broken their fast, and would carry on until midnight or even later. He left us with the suggestion that we should take a rest, as their driver would pick us up at 8.30pm to take us to their office.

The company’s driver was waiting for us in the lobby, and he drove us to the office, which was in downtown Jeddah at the corner of Gabel Street. The main business of the Mahmoud Saleh Abbar Company was provisions, so we entered its old building through cans of palm oil, bags of rice and other foodstuff. After a flight of stairs, we got to the first floor, which was their Casio department, since they were also into electronics. Casio pocket calculators, watches and organizers were popular at the time, and this meant good business for the company. The owners, who were members of the Abbar family, as well as Saleh Balahwal, had their offices on the third floor. Saleh, who looked fresh and energized after having concluded his fasting for the day, took us on a tour of the management floor, where we saluted the elder of the family, Sheikh Mahmoud, and had a sip of very sweet tea in his office. We were also introduced to his American-educated eldest son, Khalid, before settling in Saleh’s office and receiving an impressive presentation about Saudi Arabia, its history, and the religious system that continues to govern the way this oil rich country is evolving. Saleh’s explanation was passionate and very authentic. It captured our attention, although time was running fast. This overview, which I felt to be pivotal in my own Saudi Arabian journey, was a little too long for Harvey Morse, who was still jet-lagged despite the afternoon rest. Saleh carried on with his introduction of the local white goods market, the competitive brands, their successes, and failures. He concluded with another long stretch about the company’s own Westinghouse business and its plans for the brand. By that time, we were on our fourth round of sweet tea and the time was past 10pm. Harvey had begun to show signs that he was getting sleepy, so the meeting was adjourned.

Saleh personally picked us up the next morning and we drove to his office. Harvey had brought the catalogues of the company’s new ranges, so the two of them spent the entire morning discussing the kind of features that were needed in Saudi Arabia. Then, when all the technical questions were covered, a funny kind of price negotiation started, which I followed with great interest. An American export director was cornered and forced to negotiate in Saudi bazaar style. Export prices were quoted, and quantity discounts were laid with all clarity on the table before counter offers of 25 per cent and 50 per cent off the asking price were presented.

We broke for a lavish Saudi lunch at the Kandara Palace Hotel, where Harvey kept asking me in a whisper how he should react to Saleh’s unrealistic price demands without insulting him or the company. On returning to the office, Saleh ordered more sweet tea and vanished for around 20 minutes. When he returned, he announced to Harvey with a very wide smile that the Mahmoud Saleh Abbar Company was ready to double the orders that had been discussed in the morning, provided they met halfway on the prices. Harvey, with his long experience, realized that this was the best deal he was going to get on his first visit, so instantly stood up and extended his hand to Saleh. An impressive order was instantly confirmed, in real Saudi style.

The rest of the day was spent with Harvey briefing me about Westinghouse’s advertising guidelines, and Saleh explaining the features that needed to be highlighted in the campaign that Intermarkets was to develop, and the media they liked to use. Saleh also made a big issue about the Saudi statement that needed to replace the traditional Arabic normally used all over the Saudi advertising spectrum. In his briefing, Saleh stressed that none of the ads placed in Saudi newspapers were developed by Saudis, while at their company they were always keen to speak their buyers’ language. Back at the agency in Beirut, Raymond Hanna took it on himself to lead the development of the new Westinghouse campaign, which spoke to Saudis in the language they felt most comfortable with. Even though our executive creative director was a Frenchman, there were many senior executives at the agency who were Arabic language experts. Still, when the campaign was finalized, we all gathered together in Raymond Hanna’s room to conduct a final review, and this is where the agency partners drilled me on how to present the work to the new client.

I flew back to Jeddah to be met by one of Abbar’s drivers and to find that I was not booked into the posh Jeddah Palace Hotel as I had been on my previous visit with Harvey Morse. Having decided to learn about the Saudi market as quickly as I could, I did not allow this experience to hinder my excitement of winning a new key client with actions rather than words. All the time I kept reminding myself that our claim to fame, when Intermarkets was established, was that it was the first regional advertising agency for the Middle East markets. To deliver on such a promise needed people, and so far, no one else at Intermarkets was running next to me to complete the regional capability marathon. Saleh Balahwal was pleasantly surprised by the campaign material that I presented to him. He had a smile of satisfaction on his face throughout my presentation, and as soon as I suggested putting the layouts on the side and moving to the media plans, he grabbed the layouts and vanished for his classical 20 minutes. I kept looking at the door and when he came back with a wider smile, I knew that Sheikh Mahmoud had given his blessings.

My confidence peaked prematurely. As I began the discussion on media selection with Saleh, I seem to have projected arrogance. It was if I was saying, “now that they have seen how good our creative skills are; it’s time for them to hear from the agency that their existing choice of media was poor”. Suddenly, the atmosphere in the room changed and became tense. Saleh’s pleasantness vanished and he flared up, challenging my comments to the extent of saying: “How can you be so confident that you know Saudi media better, when you have only visited the Kingdom once before?” I spent the night thinking about how to win Saleh Balahwal back. In the morning, I went to meet him with the conviction that to succeed in the Kingdom one needs to be extremely polite, humble, down to earth, and honest. So, instantly I switched to a very respectful and calm tone, rather than retaliating with anger. I showed him the schedules that we had drawn exactly as per his brief. I pointed out that the rates we had quoted were the same – if not better – than the ones they had been paying when they booked the media directly. However, in what I wanted to stress was my honest style, I explained that my earlier comments were inspired by media surveys that we paid a fortune to receive on a regular basis, promising to better explain how our media planning was done on my next visit. We finally ran the campaign, which brought in noticeable results, so I quickly received an invitation to return to Jeddah.

PARC’s media surveys were sold to agencies in a computer printout format and bound in large, blue-colored plastic covers. There was a book for each country, so I carried the Saudi booklet in my suitcase and travelled back to Jeddah. That visit was phenomenal, as I spent the morning of the first day explaining to Saleh all he needed to know about media surveys, after which we studied every single page of the Saudi survey together, and this allowed me the opportunity to justify the comments that I had made earlier, and which had annoyed him. After our traditional lunch at the Kandara Palace Hotel, Saleh gave me a pile of Westinghouse product catalogues, which included a new refrigerator, an office water-cooler, and a window air conditioner, explaining that these represented the bulk of his new order, which he had recently confirmed to Harvey Morse. Saleh asked me to go back to Lebanon and prepare campaigns for the launch of the three products. I waited for him to continue his brief, but he pressed the green button and the people who had been waiting since morning to talk to him started flooding into his office. Having gained some experience on how business is conducted in Saudi Arabia, I interrupted one of his visitors to ask Saleh for more information, which was required to help Intermarkets develop the new campaign. He instantly answered, telling me that the product specifications were in the catalogues he had given me, and this is the best brief we can get. On the media selection, budget and frequencies, Saleh said: “With tools like your media survey, you are certainly better informed on what needs to be done; so, go and do it.” This became the pattern of our cooperation from that day on.

On the flight back to Beirut, I began asking myself how I could make an executive creative director and his entire team, who had never set foot on the soil of any Arab country other than Lebanon, develop a campaign that would persuade Saudis to start showing preference towards Westinghouse products beyond the advantage of features or price. At the agency, I shared the outcome of my Jeddah visit and the concern that was growing in my mind with my two bosses, Raymond Hanna, and Nahi Ghorayeb. I led the brainstorming on this challenge by dramatizing the fact that if we really wanted to make a regional agency out of Intermarkets, we could not carry on doing what we and other Lebanese agencies had always done. We needed to change, we needed to walk the talk and show a clear and highly visible difference. Keeping in mind that I was the young newcomer amongst the seasoned owners, my ideas would have been dismissed had it not been for Nahi Ghorayeb, who had struck me as a man of change when I first met him in 1968 during Arab Week’s Kangaroo Conference at Al Bustan Hotel in Beit Mery.

Nahi and I met independently and attempted to identify an umbrella theme around which the new product launches could be pegged. A theme with universal appeal that would surprise Saudi readers and linger in their minds due to its originality, keeping in mind that they were used to ads featuring product shots and superlative headlines. At the same time, winning the acceptance of Westinghouse’s management, legal department, and global marketing team, as well as Sheikh Mahmoud Al Abbar. Historically, this period was known as the Cold War, and this name had become an integral part of media headlines all around the world. So, Nahi and I called Gabriel Brenas and asked him to develop a campaign under this theme and to convert it into an impactful and memorable campaign idea. Soon, the first ad appeared from the mezzanine floor studio, and it showed an open spacious Westinghouse refrigerator on whose shelves – and in place of the usual food and drinks – were terrestrial globes (like the ones used in geography classes or placed on the desks of international export managers) with a headline that said: “The warm world seeks cool shelter inside the new Westinghouse refrigerator.”

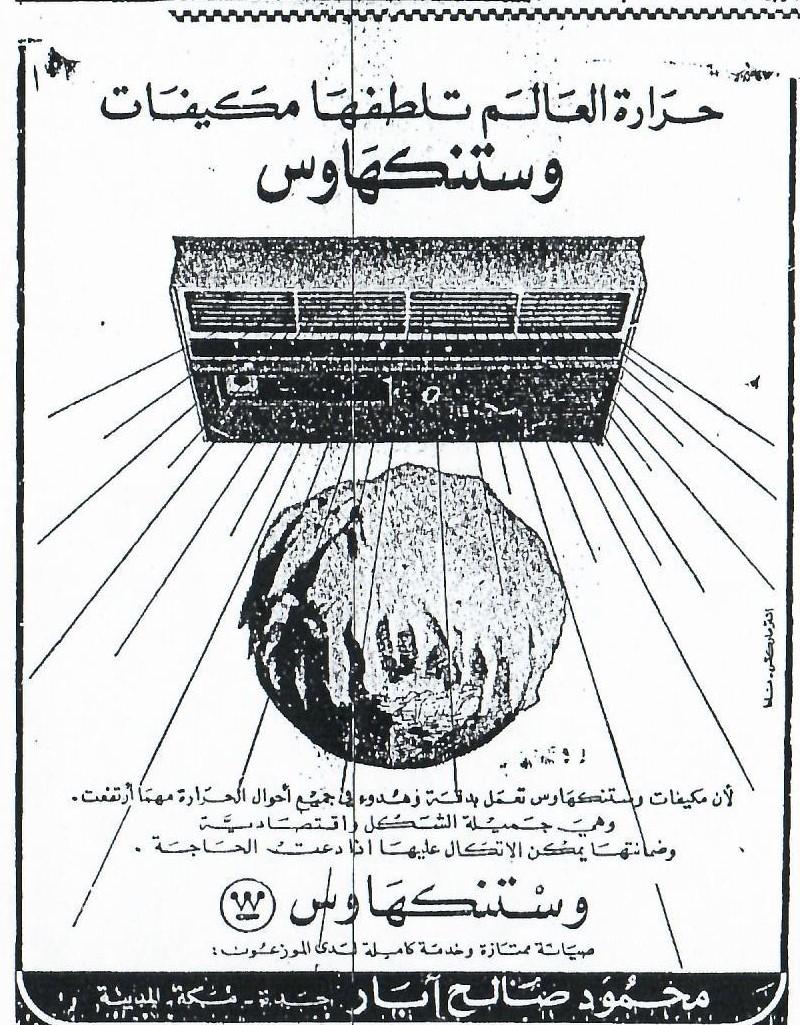

We all loved the idea, so a similar treatment was done for the air conditioners, which featured one blowing icy clouds at the globe, and the water cooler spurting its cold water into a mouth that had been placed on the globe.

The campaign was loved by all, particularly the client in Saudi Arabia and the US, as well as the media and the public in the Kingdom.